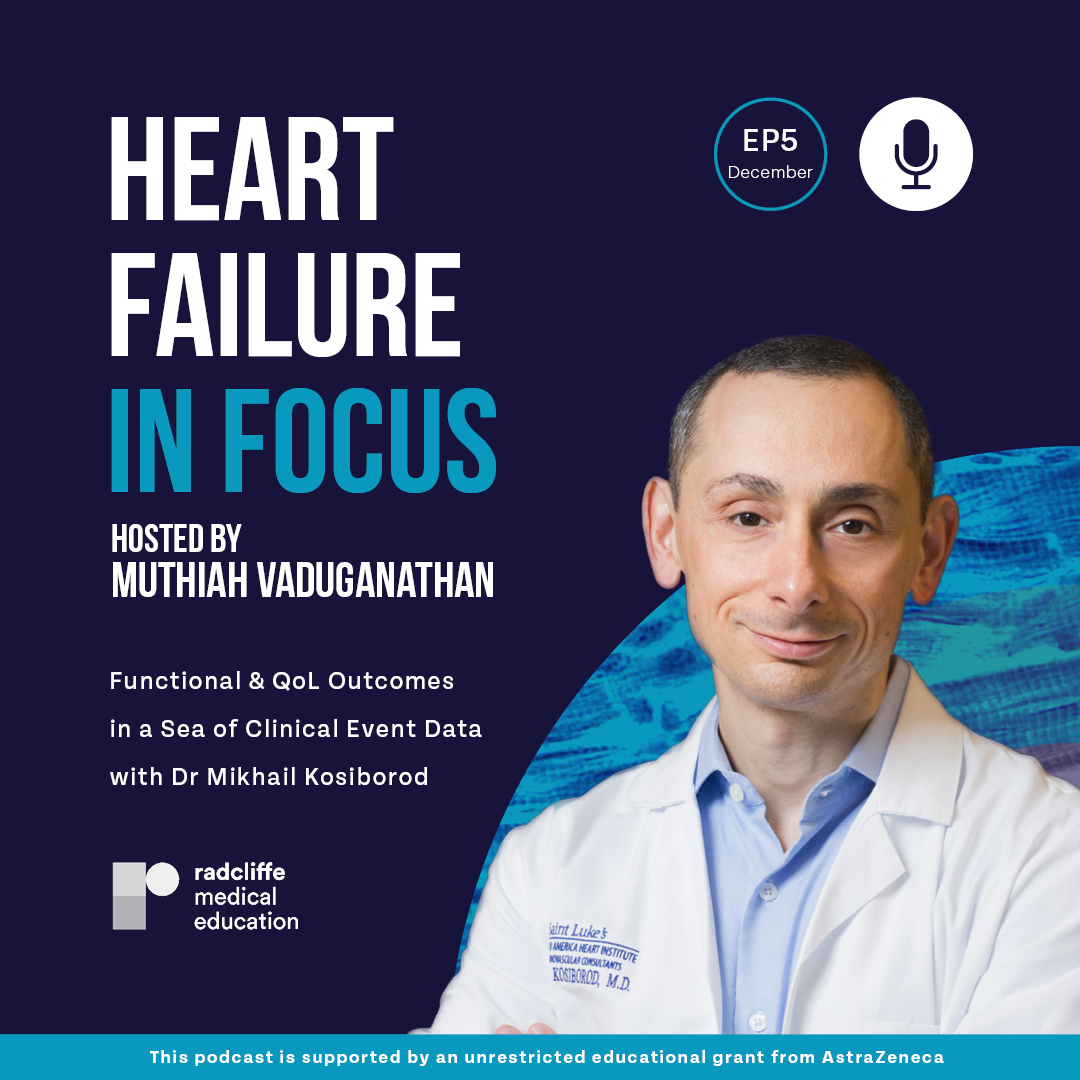

This month we are joined by Dr Mikhail Kosiborod, clinical trialist, Professor of Medicine at St Luke’s Heart Institute and leading expert on Quality of Life (QoL) instruments worldwide.

Dr Kosiborod discusses functional and QoL outcomes of foundational therapies in Heart Failure (HF) and the clinical application of this data. Additionally, we learn how scoring systems like the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) can be used to establish clinically meaningful change in functional status. Finally, we consider how regulators future guideline development might start to look beyond the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification and embrace QoL and overall health status when assessing HF treatments.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

Listen to more episodes from Heart Failure in Focus.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

The first episode will be launched on 28th August. Watch this space!

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Questions can be sent via Twitter to our host @mvaduganathan or to @radcliffeCARDIO.

This podcast is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Participants: Dr Muthiah Vaduganathan and Dr Mikhail Kosiborod

Episode: December 2022

Please note that the text below has not been copyedited.

Dr Muthiah Vaduganathan:

Welcome to this episode of Heart Failure in Focus. I'm your host, Muthiah Vaduganathan. This podcast is hosted by Radcliffe Medical Education, and is supported through an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca. Please note this podcast is intended for healthcare professionals.

Welcome back to this episode of Heart Failure in Focus, and I'm really delighted to have a close, close friend and luminary in cardio-metabolism and clinical trials, Dr Mikhail Kosiborod, to join us for a special on Quality of Life in Heart Failure. He is a Clinical Trialist Professor of Medicine at St. Luke's Mid America Heart Institute, really the namesake and perhaps a central hub for quality-of-life instruments worldwide. And it's really a delight to have you, Mikhail. Thank you so much.

Dr Mikhail Kosiborod:

Muthiah, it's a pleasure to be with you. Thanks for having me.

Dr Muthiah Vaduganathan:

Mikhail, we have had many, many discussions over the years on this topic, and so I'm going to dive right into some of the more challenging ones that often come up from people in the community. So often people wonder, when they look at pivotal randomised clinical trials, once they report, that average differences in quality-of-life instruments, such as the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, are often modest and perhaps fall below what we may consider clinically meaningful. And so how do you interpret those data, and how do you actually respond to those comments? And in your view, do typical guideline directed medical therapy, do they actually improve quality-of-life based on those data?

Dr Mikhail Kosiborod:

Right. Well, it's a great question, Muthiah. And in fact, comparing the effect of what we consider to be efficacious, even foundational therapies in heart failure, are sometimes a bit difficult; not just because of the usual reasons we give about comparing different medications to one another because the trials are designed differently, and patient populations may be somewhat different as well. But you've got to keep in mind that back in the days when the initial foundational therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in particular were developed... like beta blockers and RAAS blockers, in particular like ACE inhibitors... quality of life or health status measures, as we call it today, were either not routinely used in clinical trials at all; or if they were used, they were not necessarily the same instrument with what they consider to be a gold standard today.

And we have several instruments. You mentioned KCCQ, which I think now has become the gold standard, the results in Minnesota Living with Heart Failure, and they do differ. While they're both good at evaluating health status at baseline, there are quite a few differences between them if you look at how responsive they are to clinical change over time, for example; which is a critical question, of course, in the heart failure trials. There are some challenges in comparing different medications, if you will, in terms of the effect on quality-of-life instruments or health status instruments.

With all of those limitations acknowledged, I think there are a couple of things to keep in mind. They're definitely not all the same. While they may have comparable effects on reducing cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalisations in some cases, or at least in the same ballpark, they're not all the same when it comes to effects on symptoms, physical/functional quality of life. And of course, those outcomes are very important; they're very important to patients and also clinicians. Ultimately, that's why patients come in to see us, right? They come in to see us because they're not feeling well and they want to feel better.

And actually, for some classes of medications there is no compelling data that they improve, at least in the short-term, quality of life at all. Probably a great example of that would be beta blockers. That means they're clearly fantastic medications for reducing death and hospitalisations, but there isn't really any compelling data that quality of life improves in patients with heart failure with reduced EF. And heart failure with preserved EF, withdrawal of beta blocker actually makes people feel better. So there are definitely differences between them, and so not all the same, no question about it. That's the first answer to your question.

The second part, which is what do we actually/ how do we use those numbers, and why is it that in many trials the numerical differences between the two interventions... drug and placebo, for example, or drug inactive comparator... are what's viewed as relatively modest and below the threshold, five-point threshold, for clinically meaningful change. And I think here it's critically important to understand that this five-point clinically meaningful difference is really not supposed to be applied when we look at the differences between large populations of patients. Of course, the way we do trials is there are thousands and thousands of patients, and we look at averages across those populations of patients. And while it's important to understand if the drug is better than placebo or active comparator when we look at these main differences, those main differences across thousands of patients don't really tell the true story of what the effect of this medication is on health data. What you really need to look at is, on an individual patient basis, what happens. On an individual patient basis, a five-point threshold is meaningful, but on population level it really isn't.

I personally think a more important or more insightful way of looking at the data is to try to understand what proportion of patients had small, moderate and large improvements, and what proportion of patients got worse instead of better on the active intervention versus a comparator, and that I think tells you, really, a better story. I'll give you just one example, of course you know, I'm partial to SGLT-2 inhibitors, because I was quite heavily involved in that whole story. But we did a trial called PRESERVED-HF in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction with dapagliflozin versus placebo, dapagliflozin of course being one of the SGLT-2 inhibitors; and we found that, as there was more than double the proportion of patients treated with dapagliflozin, and certain patients with heart failure, and mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction, more than double the proportion of those patients had very large improvements in health status, in KCCQ, as compared to those treated with placebo. That I think is the kind of information you want to look at when you try to understand, "Are these medications really effective in improving how patients feel and what they're able to do?"

Dr Muthiah Vaduganathan:

Brilliant overview and congratulations on those trials. I think you've pioneered many of the trials that have set the stage for application of quality of life in heart failure trials. You've talked about clinically meaningful; and so when we reference mortality/hospitalisation outcomes, we often talk about effect sizes in the order of 15%, 20%, 30% reductions in those, relative reductions in those events, and in general these therapies align in producing those effects at the population level. How do you think about clinically meaningful differences in quality of life, or other measures of health status, and how is... Let's take the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. As you mentioned, it's really become and risen as the gold standard. How is five points selected? Why was that selected as clinically meaningful to patients?

Dr Mikhail Kosiborod:

Right. Well, as you well know, the person who actually developed the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, who's a good friend and colleague of mine right here at my institution, St. Luke's Mid America Heart Institute, John Spertus. John and his colleagues did a very thorough evaluation of this where they actually measured KCCQ serially, and they also looked at serial changes in the patient clinical status; and what they tried to do is correlate again on individual patient basis, really tried to correlate and understand what changed from an individual patient basis in KCCQ, correlated with what the clinicians would consider to be a meaningful change, and in patients' overall clinical status, and that's really where these data come from.

And that's why what I mentioned earlier, which is the way it was developed, the way the clinical meaningful change was generated, was not necessarily intended to be viewed as a threshold for determining effectiveness on clinical trials. I think it makes sense when you do this responder analysis where we took a proportion of patients that get worse and get better; that's where the threshold again makes sense. But when they look at mean differences across populations, it's a lot less meaningful because there is so much. Of course, as you know, when you look at thousands of patients, there is so much variability that happens.

The other point that I think is really important is: remember, when we do clinical trials for patients with heart failure, outcome trials in particular, patients are being selected based on their risk of clinical events, and the predictors of those clinical events, because these tend to be event driven trials. We look at various clinical indicators, and probably one of the best predictors that we use, most reliable one, is natriuretic peptides, right? Because you can dial up your NT-proBNP or dial it down, depending what kind of events rate you want.

But what's important to keep in mind is that while there is a correlation between NT-proBNP and KCCQ, for example, if you're selecting patients based on natriuretic peptides, and you're saying, "We're going to only take people that have an NYHA Class II and Class III," which is fine, or Class II and above, is the correlation between NT-proBNP, and even NYHA class and KCCQ is not perfect by far. And what ends up happening, if you look at these large outcome trials, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire scores tend to be relatively high; which means patients, at least the way they're telling us, from their perspective, are really just mild to moderately symptomatic. And just as it would be difficult to show a large benefit when you're looking at patients at very low risk for events in event-driven trials, it's more difficult to show a clinical benefit on health status, on quality of life, when you take patients that are only mild to moderately symptomatic.

I think I mentioned the PRESERVED trial before, but PRESERVED had KCCQ as their primary endpoint, and the KCCQ in that trial was quite a bit lower than what you see in outcome trials, and the benefit was much larger. Now that makes logical sense, but that's another thing which I think it gets missed when people look at these results and say, "Well, there's 2.5 point or 3.0 point difference between the groups." But of course, keep in mind that if you take patients that have really poor health status to begin with, they will have a larger improvement.

Another example of trials, again going back to SGLT-2 inhibitors, are patients who are hospitalised, who have very poor health status. We see numerically larger attack sizes in KCCQ in those trials than we do in chronic ambulatory kind of "stable." I don't like the term stable heart failure because there's no such thing, but they're more stable than hospitalised patients. Let's put it that way.

Dr Muthiah Vaduganathan:

Yes. Critical points. I think that the main takeaway there is that many of these trials are designed for clinical events and not quality of life, and so perhaps underestimate the benefits on quality of life in general. And so as a quick follow-up on that concept, really our guidelines, our regulatory labelling, is shaped largely around clinical events, and often actually specifies clinical events that may be prevented with use of a given therapy, whether a drug or device. And often quality of life, or health status even symptoms, are either not mentioned, or perhaps embedded in the supportive text of these documents, and so how do you foresee?

In clinical decision-making, in practice, of course we want all these aligned. We want therapies that improve clinical outcomes, such as quality of life, and also hospitalisation/mortality outcomes. But in certain circumstances, there is some discordance, or at least out-sized benefits on quality of life and health status. How do you foresee the future of guideline development? Do you see a role for guidelines to actually make recommendations on therapies that actually improve health status, but may not have a perhaps important or measurable impact on hospitalisations or mortality?

Dr Mikhail Kosiborod:

Fantastic question, Muthiah. And I'll start by saying there's actually an incredibly insightful study; and it's one of several, but I think it's one perhaps that makes that point as clear as possible, which is when you actually ask the patient, "What's more important to you?" patients with heart failure, "What's more important to you?" and if you were to... Actually, this study was done on patients with heart failure, where they were discussing with the patients a trade-off of mitral valve surgery, if they had significant mitral registration, and the upside of potentially improving their symptoms over time by having a surgery, versus the risk of surgery, which includes potential risk of dying, or having bleeding complications, and things like that. And what was incredibly insightful from that study is that there clearly was a cadre of patients that would trade longer survival for better quality of life. In fact, they were willing to accept increase in mortality due to surgery in north of 9%, as long as they could have better symptoms, improvement in symptoms, physical function, and quality of life.

And in fact, when you account for patients' preferences on the health status, the whole conversation about hospitalisation for heart failure actually became not meaningful anymore. It was really all driven, this whole reduction of hospitalisation from a patient standpoint, was driven by improvement in symptoms. So the bottom line is patients, many of our patients, value how they feel and what they're able to do more so than how long they live, so the patients clearly think it's super important.

The regulators, I know you mentioned the regulators, they clearly have come around, and now formally acknowledged. Certainly, the USFDA have formally acknowledged that assessments of patients' health status and function are super important; and in fact, under certain circumstances, may be considered as a provable endpoint. And KCCQ has actually been qualified as potentially a provable endpoint in patients with heart failure. So obviously, it needs to be in a context also of what happens with clinical events. In other words, these interventions that improve health status shouldn't have a negative impact on survival and hospitalisation; but it's by itself, in its own right, a provable and important endpoint.

Now when it comes to guidelines in clinical practice, I think that's where the gaps are. The guidelines unfortunately haven't come nearly as far; and I think, in fact, some guideline developers will clearly acknowledge that an outcome like mortality is still more important than anything else and drives a lot of the decision-making. But I think the guideline developers, because the guidelines are so important in driving clinical practice, really needs to not just mention quality-of-life measures somewhere on page 250 of the document, but actually base their recommendations in part on what happens to that important outcome because it's so critical for patients. We all say we're obviously here to take care of patients, so that's got to have influence.

I'll give you a hypothetical example. Let's say a Drug A and Drug B both have minimal impact on mortality. They both significantly, in a meaningful way, reduce heart failure hospitalisation, but one has a much larger impact on patients' symptoms and quality of life, and the other one is not nearly as impactful. I would think it would be natural for the guidelines to make a differentiation between the two because the triple goal of care is to reduce death, prevent hospitalisation, improve quality of life, so all of those three need to be considered.

Actually, I would say ACC/AHA/HFSA guidelines have come so far, a little bit further, in starting to acknowledge this in a discussion in document. European guidelines haven't yet; it's still really all based on NYHA class. And it's very, very clear while NYHA is really excellent tool for predicting prognosis and baseline, it's not nearly as responsive to clinical change as KCCQ, for example; and of course, that's from a physician perspective, not a patient perspective. So I think the guidelines have a long way to go; and I think that the momentum is definitely in that direction, but it's not quite there yet.

Clinical practice is another frontier where we still have a lot of work to do, to be honest. I think KCCQ can be incredibly useful in clinical practice, and there are a number of centres that are trying to implement it in everyday care; but it certainly hasn't become a household item, if you will, in our daily assessment of patients with heart failure yet.

Dr Muthiah Vaduganathan:

Fully agree, Mikhail. And we have about a minute left, and I want to borrow your wealth of experience in running trials and employing these instruments. And so many of the listeners are going to be junior investigators, or early career investigators, embarking on this journey. And often, in an era when we're trying to streamline CRFs, and it may be daunting to employ or incorporate a multi-question instrument like the KCCQ. And so what is your response to that? And you have clearly been very effective at embedding these instruments in trials, and so can it be done in a streamlined manner, in an efficient manner that is also cost efficient for trials and for society?

Dr Mikhail Kosiborod:

Right. Well, I think the simple answer to this is that collecting any data point involves a certain amount of investment that needs to be made; and you of course want to make sure the data you're capturing is good quality data, so you want to be consistent in how you collect it. With all that acknowledged, I think first of all patients appreciate being asked how they feel. There's actually been a formal study to show that when KCCQ is embedded in clinical practice, not in the clerical trial setting, patients feel like they're more engaged, and they especially appreciate the discussion about the KCCQ results with their clinician, and they feel like that makes a meaningful difference in their management. And so same is true in a clinical trial. Patients actually, as long as you make it user friendly and easy for them, and it's not a huge hassle from a technology standpoint, they actually appreciate being asked.

I would say, just very quickly, there is a wealth of different ways in which cases can be collected. I mean that's the beauty of the tool is that it can be collected on paper, it can be collected on a tablet, it can be collected on a website, it can be collected through the app, and it can be collected completely remote. So John Spertus led this trial recently called CHIEF-HF, I was involved in that as well, that was done in the middle of a pandemic. Actually, it just so happened that it was planned before the pandemic, but it just so happened that it was launched the week of the pandemic declaration. And when all of the other heart failure trials came to a screeching halt, we were able to recruit the trial at a higher rate than average rate, despite the pandemic, fully remote with the primary outcome of KCCQ that was collected through the app. That's another beauty of the tool is that it just... you know, don't even have to see the patient at the centre, at the clinical site, the trial site, in order can be able to collect it. And nowadays, most patients have their smart devices, and the app actually works incredibly well.

The last thing I will say is that John and his group also have done a lot of work in trying to simplify KCCQ. There is now what's called the KCCQ-12, which has 12 questions instead of the 23 standard KCCQ questionnaire. So as everything else, things will evolve and become simpler and easier to implement, but I think we usually don't bat an eyelid doing things like echocardiograms, or sending patients to get blood work done for natriuretic peptides, but... And this was actually, I think in the spectrum of things we do in clinical trials, relatively straight forward.

Dr Muthiah Vaduganathan:

This was such a delight of a conversation. Thank you, Mikhail, for allowing us to borrow your time and expertise, and in-depth experience with quality of life and heart failure.

And thank you all for listening to this episode of Heart Failure in Focus. We look forward to sharing with you the next episode.

Dr Mikhail Kosiborod:

Always a pleasure, Muthiah.