There will be guidelines about the optimal management of most clinical situations. It makes decision making in medicine more universal, but often you have to think about all of the awkward situations that sit outside the guidelines. One neglected area of research involves the management of illness in older people. The older patient is often not included in trial protocols, and so a well of knowledge is absent for an ever-increasing number of patients. There is an assumption that extending the existing data, acquired from trials conducted on patients sometimes two or three decades younger, to the older individual is adequate.

Whatever the clinical scenario, two sides of the argument exist: ‘just because they are old does not mean they should not have what is appropriate’ and ‘these invasive tests are inappropriate and an unkind thing to do to an older person’. This argument underlies the daily predicament of increasingly older patients with multiple comorbidities presenting with coronary syndromes. The challenge for the cardiologist is in making the appropriate decision in every case.

Epidemiology, Comorbidities and Frailty

Nutritional and medical advances have increased longevity. Definitions based on chronological age are crude, as biological ageing differs between individuals, but if we use 80 years or above as our marker, the proportion of octogenarians is expected to triple by 2050.1 Not surprisingly, there is an increasing incidence of octogenarian patients presenting with stable angina and acute coronary syndromes.2,3

It is now entrenched in law that age alone cannot influence any aspect of the decision-making process, yet ageing is a fundamental factor to consider when determining the appropriateness of a medical intervention. It requires the physician to use the available tools in an appropriate manner and consider the whole range of comorbidities before choosing a strategy for the presenting problem. Older people are a different cohort of patients, as the deterioration of various organs has a detrimental effect on vision, hearing, mobility, renal function, cerebral function and cognition.4–6 All of these factors individually or in combination can contribute to a final management plan.

It is true of many interventions, but particularly cardiac interventions (structural and coronary), that successfully resolved cardiac symptoms may have little impact on the overall burden of other morbidities, and so the overall improvement in the patient’s quality of life is marginal. Thus, when considering invasive or surgical intervention in the older age group, it is important to emphasise that any favourable impact on the patient’s clinical outcome and quality of life will be limited to the resolution of his or her cardiac symptoms.7–9

Frailty reflects a reduction in physiological reserve and is widely recognised as a predictor for poor health outcomes in the older population.10 It is difficult to define frailty in a satisfactory and comprehensive manner. Is it a physical component dependent on nutrition and muscle bulk that influences strength and endurance? Or is it mental, affecting mood and cognition? More than 20 scoring systems and diagnostic tools have been devised to quantify frailty and its impact on outcomes with regards to cardiovascular disease.11 Some of these tools, such as the Charlson index12 or the outcome-based frailty index13 can be extremely helpful when attempting to decide on how aggressively to manage an older person. Upward of 40 studies were published in the 4 years between 2010 and 2014 attempting to address frailty in the context of cardiovascular disease;11,14,15 however, none were able to encompass the vast scope and spectrum this term covers.10

Although the majority of the above studies assessed mortality following a cardiac event or procedure,11,14,15 it is important to note that many of the older population will value quality of life over mortality risk or benefit, in essence wanting quality rather than quantity. Using percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to treat symptoms reduces hospital readmissions but leads to increased frailty physically, through loss of muscle bulk, and mentally, through loss of confidence.16 The trajectory of the frailty may also vary, not only through the event but with the treatment option adopted: PCI versus coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) versus medical therapy.17

There is an age-related decline in cognition, and an increasing likelihood of dementia over time.4–6 The presence of cognitive decline makes treatment decisions difficult, as these matters are rarely binary and the rate of decline can be very variable. The authors believe, however, that it is generally accepted that cardiac interventions in patients with dementia are rarely appropriate. This can raise challenges in the acute setting, when patients require emergency angioplasty for ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), or emergency pacing, when the lack of opportunity to discuss the broader context might lead to inappropriate intervention.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Older People

Revascularisation strategies for patients with stable angina and the acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are based on multiple trials and are coalesced within guideline recommendations from various associations.18–20 These trials are based on patients with a mean age of about 60 years. There are many subgroups of patients that benefit from surgical revascularisation, with evidence for improved survival, but when it comes to the prospect of an octogenarian undergoing surgery it is the morbidity and recovery that are the main stumbling blocks. For example, permanent diasability due to stroke is much more likely in octogenarian patients undergoing CABG when compared with PCI (2.84 % versus 0.57 %),21 and so many of these patients undergo PCI as a suitable alternative.

Coronary Syndromes

Stable Angina

The older patient is more likely to have multivessel disease, calcified and tortuous anatomy, chronic total occlusions, poor left ventricular function, renal impairment and concomitant valvular disease. Fortunately, there is little coronary disease that cannot be treated by percutaneous means. Remarkable technological advances allow the modern interventional operator to deal with obstructive calcium, rigid tortuosity, challenging left main coronary anatomy and chronic total occlusions with little collateral complication.8

Although the Trial of Invasive versus Medical Therapy in Elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary-artery disease (TIME) is dated, it stands out as the only randomised-controlled trial comparing medical therapy to invasive management in older patients with stable angina. A relatively small number of patients (305 patients, >75 years) with symptomatic chronic stable angina were randomised to invasive investigation and treatment (PCI or CABG) or optimal medical therapy. At 6 months the investigation and treatment group had better symptom relief and quality of life, in addition to having fewer major events, when compared to the medical arm (49 % versus 19 %).22

Analysis of the UK PCI (British Cardiovascular Intervention Society/ National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research) database shows that major adverse cardiac event rates for older patients with stable angina are low and compare favourably to a younger cohort. Often the function of intervention is resolution of difficult symptoms, however, and pursuing strategies for longer-term mortality benefit when one is >80 years of age is difficult to justify, particularly when the intervention involves major heart surgery. There is a small amount of literature on highly selective patients demonstrating good mortality results from cardiac surgery,23 but it is often the morbidity of surgery that leaves the older patient reeling.

Non-ST Segment Myocardial Infarction

The main trials that steered the management of patients to an invasive strategy with a view to revascularisation had cohorts with a mean age of 61 years,24–26 and the concept that all patients should have angiography and revascularisation if appropriate is enshrined in cardiac practice. A meta-analysis has shown that the benefits were greater in the older patients within the various trials,27 but it is unclear where the benefit gained starts to flatten out. The line cannot continue to be straight and upward. Indeed, as many physicians think it inappropriate to subject older patients to invasive investigations and treatment as think it criminal not to. Each patient deserves to be judged on his or her individual performance status, as biological age often does not represent chronological age. There is considerable individual variation in relation to the presence of comorbidities and physical capabilities.

Octogenarians are woefully under-represented in the trial data, and where there are data, very few come from randomised-controlled trials.28 Most data come from large registry data sets.29,30 In initial trials published including data from the Non-ST-Segment Elevation – ACS (NSTE-ACS) European registry, roughly a third (27–34 %) of patients are aged ≥75 years, but this proportion has dropped to no more than 20 % of all patients in recent trials. Even when older patients are recruited into clinical trials, they are highly selected, often having substantially less comorbidity than patients encountered in daily clinical practice.31 –33

The rate of mortality for those aged >75 years is twice that of those aged <75 years and the prevalence of ACS-related complications, such as heart failure, bleeding, stroke, renal failure and infections, markedly increases with age.34 In addition to this, the older patient is less likely to be treated invasively.35 A subgroup analysis of the Treat angina with Aggrastat and determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy – Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TACTICS-TIMI 18) trial, however, found that patients >75 years of age with NSTE-ACS derived the largest benefit, in terms of both relative and absolute risk reductions, from an invasive strategy at the cost of an increase in risk of major bleeding and need for transfusions.28 There are on-going randomised prospective multicentre trials attempting to address the lack of research data. The Revascularisation or Medical Therapy in Elderly Patients with acute angina syndromes (the RINCAL study, NCT02086019) is actively recruiting and randomising patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction to initial conservative management with a view to invasive assessment and treatment if conservative measures fail versus invasive assessment for all, thus including angiography as part of the management whatever the clinical circumstance. The primary endpoint is death from cardiovascular cause and myocardial infarction at 1 year. The results of this study will be available in 2018.

STEMI

Immediate PCI for patients with STEMI is now the treatment of choice, if appropriate expertise is available to perform it in a timely manner. Older patients have more to gain from primary angioplasty, but they can provide a challenge to the interventionalist as they are more likely to be sicker, have less ventricular function to work with, have an increased likelihood of significant comorbidity and have more challenging coronary anatomy. There has to be some judgement about appropriateness in each case, but often the lines are blurred about clinical appropriateness, particularly when decisions to treat have to be made quickly in order to secure the benefit.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation offer no specific guidance for octogenarians.36 The guidelines do, however, acknowledge that these patients are at a higher risk of side effects from medical treatment, including the risk of bleeding following treatment with antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants, hypotension, bradycardia and renal failure. In addition to the intrinsic bleeding risk of older people, as a group they are more frequently exposed to excessive doses of antithrombotic drugs that are excreted by the kidney, which can cause a problem due to age-related decline in kidney function.36

Data from the Myocardial Infarct National Audit Project (MINAP) in the UK show substantially differing management practices in different centres. The IMAP analysis suggests that reduced mortality in older people was directly correlated to whether or not a primary angioplasty procedure was performed.37 It is clear that it is entirely inappropriate to deny patients treatment for their heart condition based on their age alone. Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals’ practice activates the primary angioplasty team for all STEMI patients. The only time the team does not plan to intervene urgently is when the patient has arrived in the catheter laboratory and been clinically assessed.

Multiple Drugs and Drug Interactions

As diagnoses accumulate with time, the drug list grows. With the zealous processes in place to ensure that conditions are treated with the correct plethora of drugs, the pressure to prescribe is significant. This is particularly notable for cardiovascular conditions, where optimal management for heart failure, atherosclerosis and cardiac revascularisation all involve the prescription of multiple agents.36,38 The management of cardiac disease within the older age group is riddled with the conflict between lean prescribing, with fewer interactions and side effects, and the evidence-based prescribing of high doses of multiple agents.39 Many of the trials influencing decision-making in cardiovascular medicine are based on populations with a mean age in their early 60s, however, as older age is usually an exclusion criterion because of the increased possibility of events that may be unrelated to the trial question. Thankfully, there are trials emerging that are investigating the role of medical intervention in the older age group. The results of these trials will be invaluable in guiding future decision making.

Compliance

Not surprisingly, it is more likely for the senior citizen to be noncompliant with their multiple drugs.40 One would have thought this would have implications for patients with drug-eluting stents, for example. A failure to take dual antiplatelet regimens religiously after surgery to place drug-eluting stents should lead to increased rates of stent thrombosis, although the limited data available in this age group have not shown this to be a clinical concern.31,32 Similarly, the data on the use of high-dose statins could be challenged in this age group, as older people were excluded from the statin trials on which decisions to treat are based, and there may be a counterargument that individuals in this age group run a higher risk of developing statininduced myositis.

Specific Coronary Anatomical Subsets

Calcification

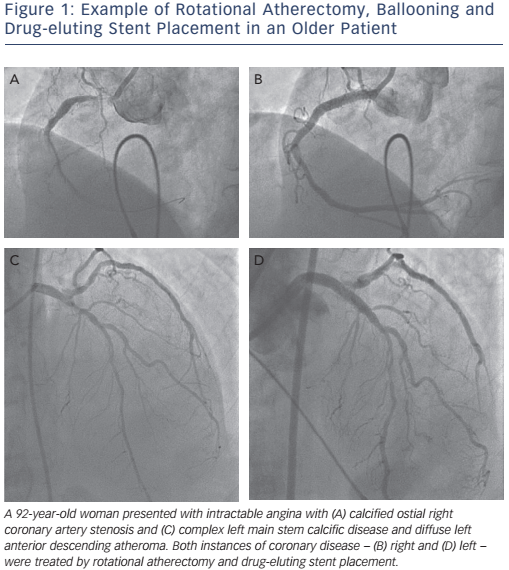

Vascular calcification is a complex and poorly-understood biological phenomenon. The idea that bony cells deposit within the vascular tree is a strange one. The condition is more likely to occur in patients with hypertension, diabetes or renal impairment and the incidence increases with age.41 There are some data supporting the belief that coronary calcification is an independent predictor of mortality.42 Any interventional operator with a sizeable octogenarian patient group will need to be adept at managing the heavily-calcified artery. The reduction in wall compliance can lead to inadequate lumen expansion with incomplete stent apposition, leading to increased rates of stent thrombosis and the requirement for target-lesion revascularisation. Lesion preparation with rotational atherectomy has reduced these unwelcome complications, but complications remain more likely.43,44 In the authors’ analysis of more than 2,000 patients undergoing rotational atherectomy prior to stenting within the UK, it was found that there was less procedural success when compared with a cohort of patients not requiring rotational atherectomy (90.3 versus 94.6 %; p<0.001) and complications were more frequent (9.7 versus 5.4 %; p<0.001). After 2.4 ± 1.2 years’ follow-up, there was slightly poorer survival for patients undergoing rotational atherectomy, even after adjustment for adverse variables and following propensity analysis.45 An example of critical coronary disease due to severe calcification and its successful management is shown in Figure 1.

Tortuosity

Tortuous vessels can provide unwelcome resistance to optimal stenting. The passage of a rigid tube around tight corners has proved problematic in some cases. Improvements in stent design and morphology, stiffer wires and mother-and-child catheters have allowed the resolution of most of these hurdles, but occasionally calcified tortuous angles remain defiant to stent placement.

When to Use Bare Metal and Drug-eluting Stents

There are a number of theoretical concerns about using drug-eluting stent technology in the octogenarian cohort. Potential problems with compliance with dual antiplatelet therapy might increase stent thrombosis rate, and the increased possibility of significant bleeding complications with the longer duration of dual antiplatelet therapy would suggest that bare metal stenting might have a role. This hypothesis was tested in the multicentre prospective Xience or Vision Stents for the Management of Angina in the Elderly (XIMA) trial comparing patients randomised to drug-eluting stents (n=399) or bare-metal stents (n=401). The XIMA trial found similar rates of all-cause death, stroke and major haemorrhage, but a reduced incidence of myocardial infarction and target vessel revascularisation in the drug-eluting stent group.31

More recently, the LEADERS FREE Investigators compared a polymerfree Biolimus-A9 drug-coated stent with a bare-metal stent in 2,466 patients considered at high risk of bleeding, many of whom were older.32 What is unique about the trial is that both arms took only 1 month of dual antiplatelet therapy. There was a reduction in the primary safety endpoint for the coated stent (9.4 versus 12.9 %) with a significant reduction in target lesion revascularisation as well.32

Finally, the SYNERGY II Everolimus eluting stent In patients >75 years undergoing coronary Revascularisation associated with a short dual antiplatelet therapy (SENIOR) trial is comparing a third-generation drug-eluting stent with a bare-metal stent in 1,200 patients aged ≥75 years undergoing coronary stenting.33 Both arms will receive the same length of dual antiplatelet therapy – 1 month for stable angina and 6 months for acute coronary syndromes. The final results will be available in 2017.33

These trials have covered new territory, with the inclusion of an increasing number of older patients helping to define evidencebased decisions. It looks increasingly likely, based on emerging evidence, that the bare-metal stent will be confined to history.

ESC Guidelines

The ESC guidelines for myocardial revascularisation were updated in 2014, and offer guidance on revascularisation strategies for patients with both stable and unstable ACS symptoms.46 Myocardial revascularisation has been subject to more randomised clinical trials than almost any other intervention, however all four ESC guidelines acknowledge a number of significant limitations with regard to their use in octogenarians. To summarise, the ESC acknowledges that:

- As a population, octogenarians are usually undertreated and under-represented in clinical trials, irrespective of presentation, meaning that if we follow the trial results we are often extrapolating data into routine clinical practice.

- Octogenarians have a higher prevalence of comorbidities.

- They are difficult to diagnose due to atypical symptoms.

- Patients are more often referred for PCI than CABG, but age should not be the sole criterion determining the choice of type of revascularisation.

- They are at higher risk of complications during and after coronary revascularisation, irrespective of modality.

Conclusion

Age does make a difference to PCI outcomes in older people, but it is never the sole arbiter of any clinical decision, whether in relation to the heart or any other aspect of health. The management of any coronary syndrome will depend on issues of frailty, appropriateness, cognition, drug interactions, compliance and the feasibility of safe revascularisation. There are specific hazards associated with PCI in older arteries, but competence with modern coronary revascularisation techniques will allow safe outcomes for the majority of patients. In practice, the key decisions are usually made before the patient enters the catheter laboratory.